...

African Safari: Near Samburu National Reserve

Little Boy Blue sandwiched between the lovely lady Dr. Aparna Bagwe and the Big Chief Dr. Basant Mishra. Pic Courtesy: Sadanand Pimprikar 22nd June, 2023...

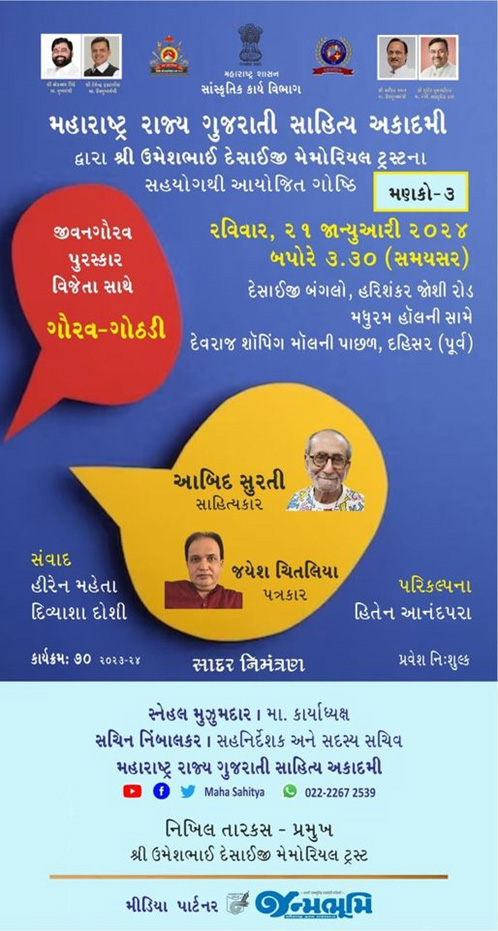

Jeevan Gaurav Puraskar

...

Urban Sanitation Hurrah Award (Delhi) 2016

...

CNN IBN Senior Citizen Award for Water (Delhi) 2013

...